We looked at all children living in the NHS Grampian region (Aberdeen City, Aberdeenshire and Moray). There were 100,000 people under age 18 in total.

We measured how many prescriptions these children had for mental health medicine. This included medicine for ADHD, anxiety, depression, sleep problems, and psychoses.

We asked these questions

What kind of medicine for mental health do children take?

Are they taking more of these medicines than before?

Are boys and girls given different medicine?

Are younger children given different medicine than older children?

What did we find?

Prescriptions to children up 60%

3% of all children had a prescription for mental health medicine in 2021.

Since 2015, the number of prescriptions has risen from 24,000 to 37,000 per year.

Sleep prescriptions are up 91%

Antidepressant prescriptions are up 59%

ADHD prescriptions are up 45%

Anti-psychotic prescriptions are up 35%

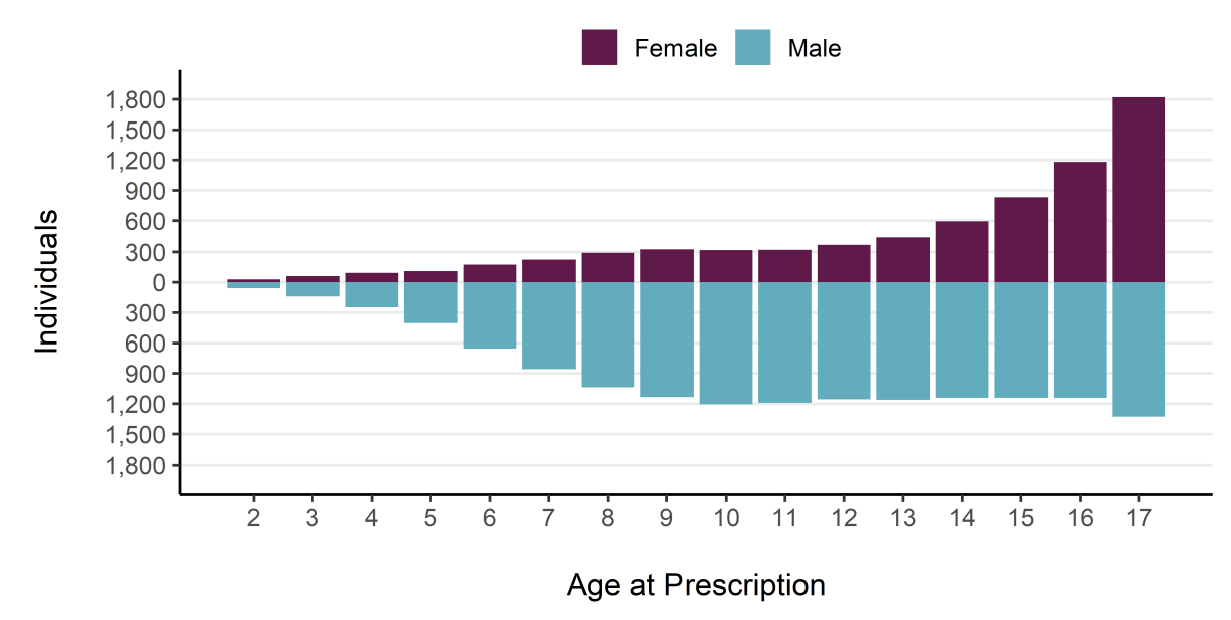

Boys get far more prescriptions than girls

Boys get 70% of all prescriptions for mental health medicine. This difference is largest in the youngest children. Boys get the vast majority of prescriptions given to primary schoolers. Girls’ prescriptions increase rapidly after age 13.

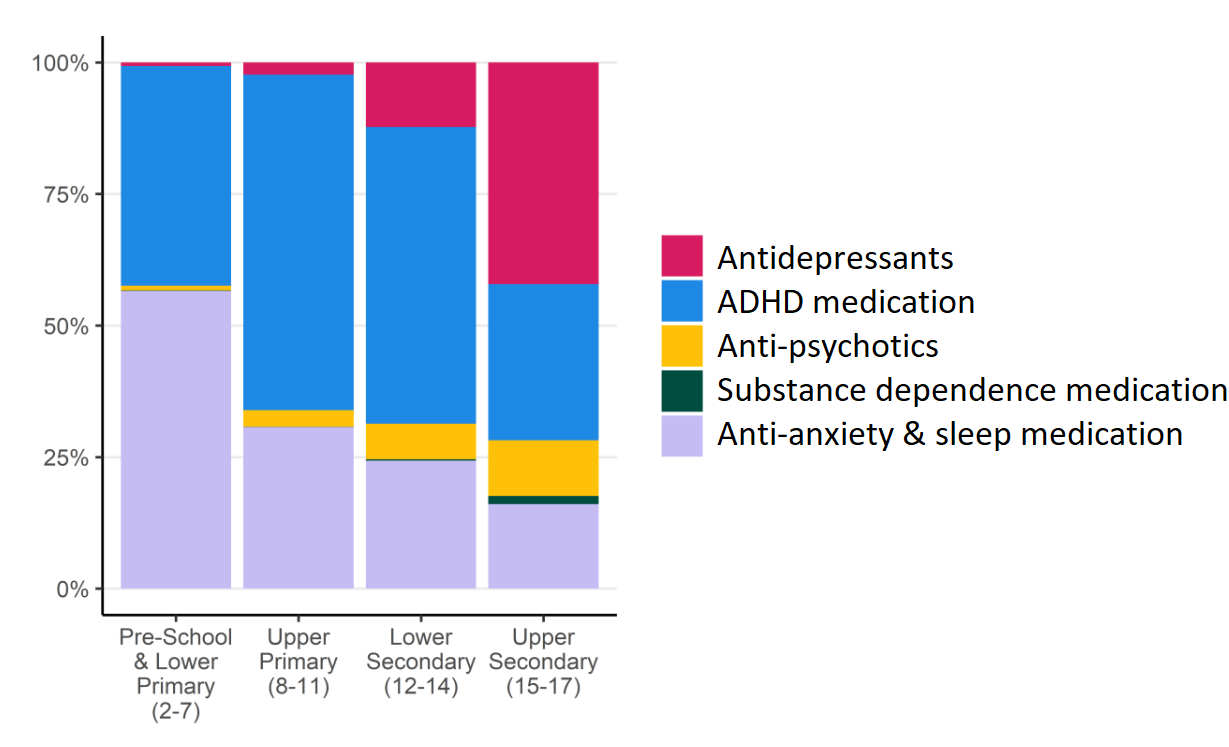

Young children take ADHD medication & older children take anti-depressants

We looked at the kinds of medicine given to children of different ages.

Primary schoolers take mostly ADHD and sleep medication. By the end of secondary school, many more take anti-depressants.

Comparing boys and girls shows that boys are given mental health medicine at younger ages, mostly for ADHD and sleep.

Girls get many more prescriptions after puberty, mostly for anti-depressants.

Children living in poverty take much more mental health medicine

We compared children living in the poorest areas to those living in the wealthiest areas. Children living in poor neighbourhoods had twice as many prescriptions for mental health problems.

For every 100 children living in the poorest areas, there were 34 mental health prescriptions every year. In the wealthiest areas there were 17 prescriptions.

Tell me more

This research was done as part of the Networked Data Lab with partners at The Health Foundation.

William Ball led this analysis with me. Other contributors from the Aberdeen Centre for Health Data Science were: Corri Black, Sharon Gordon, Bārbala Ostrovska, Shantini Paranjothy, Adelene Rasalam, David Ritchie, Helen Rowlands, Elaine Thompson, Magdalena Rzewuska, and Katie Wilde.

Full details are in our publication Inequalities in children’s mental health care: analysis of routinely collected data on prescribing and referrals to secondary care.

Policy recommendations from our work are in the briefing Improving children and young people’s mental health services